What is resilience?

Resilience is defined by the International Standards Organisation as “the ability to absorb and adapt in a changing environment”.

In cities, communities and complex organisations, this describes the ability to manage shocks and continue through disruption in the short term, and to adapt to stresses and other challenges that will present in the longer term. More resilient cities, communities and organisations will be better able to realize their strategic ambitions, through protecting critical resources, creating and sustaining opportunities for enterprise, and empowering individuals, communities and places not only to survive, but also to prosper.

Resilience has come to be known as a tool set focused on a broad range of shock and stress factors. Shocks are disruptive or harmful events that present and subside such as flooding or COVID 19 (we assume it will subside as a major issue over time); whereas stresses can be seen as changing elements of our environment and systems that over time stress or disrupt them to the point where they can no longer cope, fail or become irrelevant. Stresses can also effect the threat posed by shocks for the better or worse. An example of a stress factor is technological change, such as the advent of the internet and changing shopping habits, which quickly undermined the business models of multiple organisations including Blockbuster to Woolworths.

The current environment has been described as a perfect storm of stress factors, with ever-increasing demand for resources from a growing and aging population; an increased scarcity of supply in a wide range of key resources, including fresh water and energy; and a rapidly changing environment as a result of climate change, with a knock on impact of new diseases, and infestation of resilient fauna and flora at the expense of traditional or native species. Coupled to these three challenges are other pervasive stress factors that will impact every level of society, such as growing obesity and diabetes levels, rapidly changing technology, a widening gap between rich and poor with a direct impact on health outcomes, a perceived increase in international instability and a rise in international terrorism. In addition, globalization creates ever-greater reliance on elongated supply changes engendering ever-greater supply chain risk, and shrinking state capacity in favor of international corporations and investors.

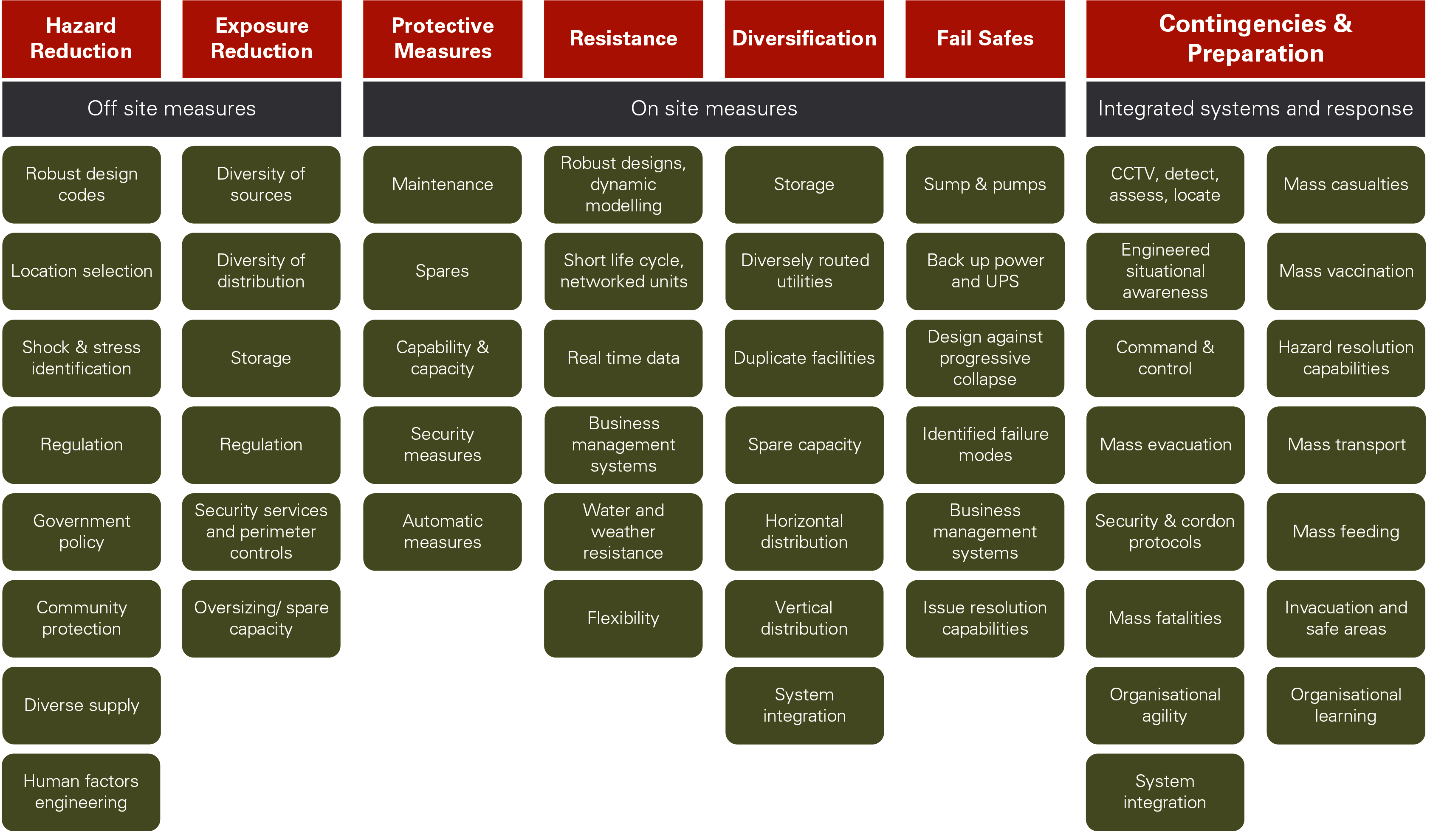

Resilience considerations can have a significant impact on design. For example, a resilience assessment performed on a large hospital in the middle-east identified a significant underestimation of the flood risk when climate change was taken into account. The design team didn’t take heed of the conclusions the data was suggesting, and designed the hospital to existing flood resilience standards. Luckily, before the construction phase began, heavy rain and flooding occurred of the magnitude predicted. The project had to be redesigned taking into account the raised flood levels. Figure 1 below shows a range of resilience interventions impacting on design decisions.

Figure 1. A range of resilience interventions impacting on design decisions.

A comprehensive resilience assessment at the start of the design process or when initiation a resilience capacity building programme with follow up throughout the programme can influence decisions at every level and also help prevent the wrong decisions being made in the name of value engineering or efficiency. Resilience principles of adaptability, integration, inclusiveness, durability and awareness can help inform decisions and reveal new options.

The methods used to provide a comprehensive resilience view are not new. What resilience thinking provides is the ability to join the dots and deliver a systematic understanding of the whole, and how it will look in the future given current understanding. This can be a powerful driver of more informed architectural and design decisions that in turn will deliver projects that are likely to deliver returns into the future and suffer fewer disruptions and losses.

Like all human endeavor resilience does suffer from the normal human biases associate with any decisions requiring foresight. It can be:

- over simplified

- viewed through a very narrow lens

- dismissed because the shocks and stresses will never happen

- seen as just too difficult to start

- given low priority because the pain of the last event if quickly forgotten

- suffer inaction because no one else is taking action

- actively resisted because it needs social change can be scary

But unlike many more traditional approaches to understanding cities, communities and organisations in their environment, resilience takes into account the human aspect of systems. It uses human factor analysis to deliver more reliable, resilient and productive systems; designing systems that take human frailties into account and valuing the contribution people bring.

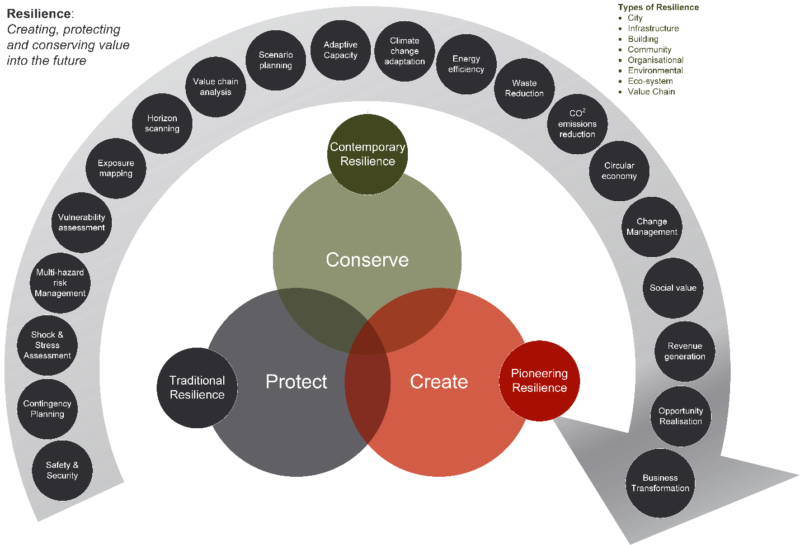

It has also come to mean everything to some and nothing to others. Resilience is very much a risk based discipline like risk management, resilience aims to create, protect and conserve value in all its forms. This understanding can be used to link this core concept to a wide range of disciplines that inform and support resilience capacity building in cities, communities and organisation as illustrated in Figure 2 below.

Figure 2. The Resilience Mix

These disciplines all inform city, community and organizational resilience, but resilience is also the golden thread that joins them together into a comprehensive and cohesive strategy or portfolio of actions that reduces the threat of failure and enhances prosperity.

Author:

Richard Look