Beyond a buzzword - the importance of resilience building and tools to build it

Resilience was the word of the year in 2022, according to the Harvard Business Review (Amico, 2022). Some speculate that this increased interest in resilience is due to COVID-19, but the interest doesn’t seem to be slowing down even as COVID’s influence dwindles. Regardless of why it’s a buzzword, it’s great that resilience is getting so much attention. Organizational resilience goes hand in hand with business continuity, and thus, it has received much attention over the years within the business continuity community, but personal resilience has only recently received the same level of awareness. As a community, we have been learning how integral personal resilience is to organizational resilience and organizational health.

With all of the information available on the topic of personal resilience, it can be overwhelming to know where to start on your resilience building journey. In this article, we will define personal resilience, discuss its importance to business continuity, and provide tangible tools that you can use to boost your own levels.

What is personal resilience?

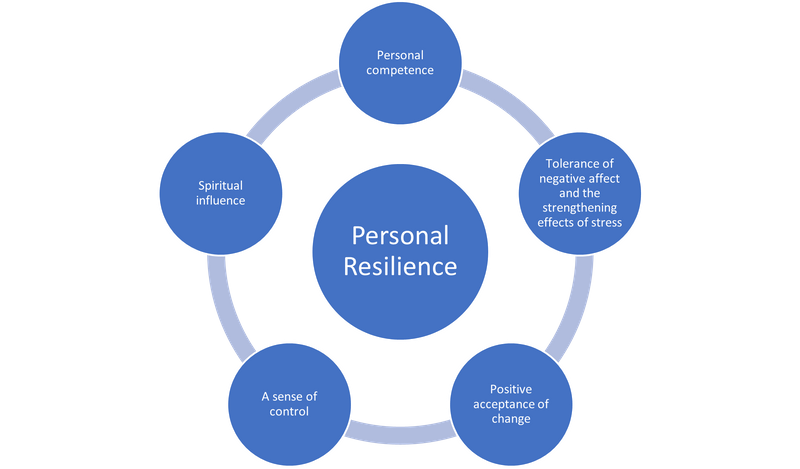

Personal resilience is an individual’s ability to handle, adapt to, and bounce back from stressful situations. There are many models of personal resilience, but one of the most common resilience measures is the Connor-Davidson Resilience Scale (CD-RISC). According to Ye and colleagues (2022), the CD-RISC has five dimensions:

Why is personal resilience important?

We are all resilient to a certain degree but research shows that higher levels of resilience have positive implications. Personal resilience can positively impact mental health by decreasing depression and anxiety. In a Forbes article written by the Resilience Institute, personal resilience was said to reduce depression symptoms by 33 to 44% (Purcell, 2020).

Another reason why personal resilience is important is its impact in mitigating the dangers of stress at work. High levels of stress at work can lead to burnout. Burnout is the psychological strain that is experienced as a result of chronic job stressors (Maslach, 1982). According to Gallup, employees who experience burnout are 63% more likely to take a sick day, 23% more likely to visit the emergency room, 2.6 times more likely to actively seek other jobs, and 13% less confident in their performance (Gallup, n.d.). To combat the dangers of burnout, organizations can focus efforts on personal resilience, as personal resilience has been shown to decrease the effect of burnout symptoms (e.g., Gupta & Srivastava, 2020).

We also need to consider the physical dangers of stress when discussing the importance of personal resilience. Around 60-80% of workplace accidents are a result of stress induced factors (Christ, 2016), therefore not properly managing stress can pose a serious threat at work, especially in high reliability organizations. Stress can also lead to heart attack, stroke, high blood pressure, IBS, diabetes, and more. Therefore, not properly handling work stress can cause permanent damage to an organization and its individuals.

An organization’s resilience depends heavily on how resilient its people are. A lack of resilient individuals can be a hazard to an organization based on the psychological and physical dangers that stress poses. And when an incident occurs, a company can have the best business continuity, crisis, and emergency response plans in the world, but if the employees are not resilient enough to handle the stressors of the job, then these plans do not matter. By increasing personal resilience, we can decrease the risk of staff shortages, decrease the occurrence of incidents, and increase the productivity of our workforce. An investment in personal resilience could be the single greatest return on investment an organization can make.

Therefore, personal resilience is more than just a trendy topic, rather it’s finally getting the attention it deserves.

How do you build personal resilience?

Personal resilience is a skill; and skills can be strengthened. There are many different tools that can be used to build resilience, but it’s important that we use tools backed by science which come from reputable sources. The following tools can be implemented to boost your personal resilience:

1. Master emotion identification

The first step in emotional regulation is emotion identification. We cannot control our emotions if we do not understand them. The ability to regulate your emotions directly relates to your resilience levels (Troy & Mauss, 2011). Many people struggle with labeling their emotions. Has anyone ever asked how you were feeling, and your answer was “I don’t know”? This is completely normal. To have better emotion identification, practice labeling all of your emotions, good, bad, and neutral. You can prompt yourself to do check-ins that consist of one simple question: “What am I feeling right now?” When able, I recommend referencing an emotion chart such as this one from Cerebral.com: the Feelings Wheel.

2. Take control of your control centre

A mindset that we can adopt to help manage stress and boost personal resilience is: “I am in control of my thoughts; my thoughts don’t control me.” A lot of individuals have an inner dialogue, sometimes called self-talk. Our self-talk is often subconscious, but if we dial into our self-talk and are intentional about what we are saying to ourselves, it can be very helpful for stress management. We can also use self-talk to prioritise our thoughts and corresponding actions during stressful work situations. When an incident occurs, focus on what you can control. Having a perception of control in a stressful situation is a key component of resilience, as outlined in the resilience definition above. It can also be helpful to prioritise the importance of certain tasks/thoughts by placing lower importance or less time sensitive items at the bottom of your mental to-do list and revisiting them when you have capacity. But if you put something on the back burner, you must revisit it, or you can fall victim to avoidance.

3. Get grateful

Gratitude has been found to increase personal resilience levels (Kumar, Edwards, Grandgenett, Scherer, DiLillo, & Jaffe, 2022). Gratitude is the expression of thankfulness or appreciation. Gratitude can promote adaptive coping and personal growth (Kumar et al., 2022), which is why it works so well with boosting resilience. We can create opportunities to express gratitude in our daily life and at work. With the emotion identification that was discussed above, when you identify a positive emotion, go one step further to ask yourself: “What am I grateful for in this moment?” You can also try maintaining a gratitude journal or keeping a gratitude note on your phone to write expressions of gratitude throughout your workday.

4. Stay present

When a stressful work situation presents itself, it’s important to remain calm and present in the moment. When we don’t remain present, we are less likely to think rationally. Psychologist Dr. Dan Siegel refers to the stress related blow-ups as “flipping your lid” – meaning that we stop operating out of our prefrontal cortex (where we think rationally and critically) and instead operate out of our amygdala (our instinctual brain which controls flight, flight, or freeze). Staying grounded or present is sometimes referred to as mindfulness and there is a lot of research pointing to the positive impact that mindfulness has on personal resilience levels (e.g., Oguntuase & Sun, 2022). There are endless mindfulness techniques that you can implement; find one that works for you and use it when you are getting stressed at work. Some examples of grounding or mindfulness exercises include:

- Breathing exercises

- Meditation

- Mantras (e.g., I am strong; I can get through this; this is temporary; I can overcome obstacles…)

- 5,4,3,2,1 anxiety countdown

- Stretching

- Muscle tense and release.

5. Embrace discomfort

We need to get comfortable with discomfort. While this may sound like an oxymoron, we’ve all been faced with uncomfortable situations and overcome them – a true testament to our resilience. We can reflect on uncomfortable situations that we’ve overcome to remind ourselves of our personal resilience. We can also seek opportunities to step outside of our comfort zone to help us grow. Overcoming adversity or an uncomfortable situation boosts confidence and personal resilience. Whenever you get through a difficult situation, be sure to celebrate the win, no matter how small. Celebrating small wins can positively reinforce our behaviors.

To seek discomfort, first, try identifying what your comfort zone is, then brainstorm some activities that would be just outside of that zone. Slowly and safely, you can work your way outside of your comfort zone. If you are looking for some examples to get you outside of your comfort zone, you can try: changing up your daily routine, eating alone in a restaurant, learning a new skill, or pushing the envelope in whatever way is meaningful to you.

In summary, if you want a more resilient organization, you must foster personal resilience. The impacts of low personal resilience levels are severe and pose a threat to both individuals and organizations. By investing in personal resilience training and providing employees with tools and resources to enhance resilience levels, you are protecting your people, environment, assets, and reputation. Through increased emotion identification, controlling thoughts, expressions of gratitude, staying present, and embracing discomfort, employees can start their journey towards increased levels of personal resilience. An important note about these tools is that they take practice. The more you use them, the more they will become second nature. As new buzzwords emerge, don’t forget about personal resilience and why it should always be a focus in business continuity practices.

Author:

Bethany Elliott, Industrial/Organizational Psychologist at CHEMTREC

References

Amico, L. (2022, December 29). Was 2022 the Year of Resilience? Harvard Business Review. https://hbr.org/2022/12/was-2022-the-year-of-resilience

Christ, G. (2016, May 7). Burnt Out: Stress on the Job. EHS Today. https://www.ehstoday.com/health/article/21917550/burnt-out-stress-on-the-job-infographic

Gupta, P., & Srivastava, S. (2020). Work–life Conflict and Burnout Among Working Women: a Mediated Moderated Model of Support and Resilience. International Journal of Organizational Analysis.

How to Prevent Employee Burnout (n.d.). Gallup. https://www.gallup.com/workplace/313160/preventing-and-dealing-with-employee-burnout.aspx

Kumar, S. A., Edwards, M. E., Grandgenett, H. M., Scherer, L. L., DiLillo, D., & Jaffe, A. E. (2022). Does Gratitude Promote Resilience During a Pandemic? An Examination of Mental Health and Positivity at the Onset of COVID-19. Journal of Happiness Studies, 23(7), 3463-3483

Maslach, C. (1982). Understanding Burnout: Definitional Issues in Analyzing a Complex Phenomenon. In W. S. Paine (Ed.), Job Stress and Burnout (pp. 29-40). Beverly Hills. CA: Sage.

Oguntuase, S. B., & Sun, Y. (2022). Effects of Mindfulness Training on Resilience, Self-Confidence and Emotion Regulation of Elite Football Players: The Mediating Role of Locus of Control. Asian Journal of Sport and Exercise Psychology, 2(3), 198-205.

Purcell, J. (2020, September 14). Resilience: The Key to Future Business Success. Forbes. https://www.forbes.com/sites/jimpurcell/2020/09/14/resilience-the-key-to-future-business-success/?sh=2c63673d5fde

Troy, A. S., & Mauss, I. B. (2011). Resilience in the face of stress: Emotion regulation as a protective factor. Resilience and Mental Health: Challenges Across the Lifespan, 1(2), 30-44.

Ye, Y. C., Wu, C. H., Huang, T. Y., & Yang, C. T. (2022). The Difference Between the Connor–Davidson Resilience Scale and the Brief Resilience Scale when Assessing Resilience: Confirmatory Factor Analysis and Predictive Effects. Global Mental Health, 9, 339-346.